Bhagavadpada Acharya Sankara was not only a great thinker and the noblest of Advaitic philosophers, but he was essentially an inspired champion of Hinduism and one of the most vigorous missionaries in our country. Such a powerful leader was needed at that time when Hinduism had been almost smothered within the enticing entanglements of the Buddhistic philosophy, and consequently, the decadent Hindu society came to be disunited and broken up into numberless sects and denominations, each championing a different viewpoint and engaged in mutual quarrels and endless argumentations. Each Pundit, as it were, had his own followers, his own philosophy, his own interpretation; each one was a vehement and powerful opponent of all other views. This intellectual disintegration, especially in the scriptural field, was never before so serious and so dangerously calamitous as in the times of Sankara.

It had been at a similar time, when our society was fertile for any ideal thought or practical philosophy to thrive, that the beautiful values of non-injury, self-control, love and affection of the Buddha had come to enchant alike the kings and their subjects of this country. But the general decadence of the age did not spare the Buddhists either. They, among themselves, precipitated different viewpoints, and by the time Sankara appeared on the horizon of Hindu history, the atheistic school of Buddhists (asadvadis) had enticed away large sections of the Hindu folk.

It was into such a chaotic intellectual atmosphere that Sankara brought his life-giving philosophy of the Non-dual Brahman of the Upanishads. It can be very well understood what a colossal work it must have been for any one man to undertake in those days when modern conveniences of mechanical transport and instruments of propaganda were unknown. The genius in Sankara did solve the problem, and by the time he placed at rest his mortal coil, he had whipped the false Buddhistic ideology beyond the shores of our country and had reintegrated the philosophical thoughts in the then Aryavarta (India of ancient times). After centuries of wandering, no doubt richer for her various experiences but tired and fatigued, Bharat came back to her own native thoughts.

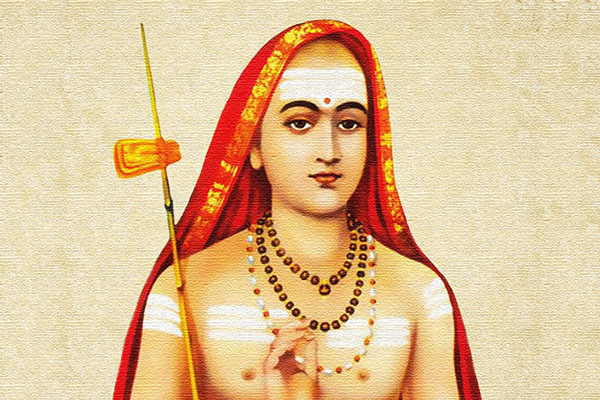

In his missionary work of propagating the great philosophical truths of the Upanishads and of rediscovering through them the true cultural basis of our nation, Acharya Sankara had a variety of efficient weapons in his resourceful armory. He was indeed pre-eminently the fittest genius who could have undertaken this self-appointed task as the sole guardian angel of the rishi culture. An exquisite thinker, a brilliant intellect, a personality scintillating with the vision of Truth, a heart throbbing with industrious faith and ardent desire to serve the nation, sweetly emotional and relentlessly logical, in Sankara the Upanishads discovered the fittest spiritual general. It was indeed a vast programme that Sankara had to accomplish within the short span of about twenty effective years: for at the age of thirty-two he had finished his work and had folded up his manifestation among the mortals of the world.

He brought into his work his literary dexterity – both in prose and poetry and in his hands, under the heat of his fervent ideals, the great Sanskrit language became almost plastic: he could mould it into any shape and into any form. From vigorous prose heavily laden with irresistible arguments to flowing rivulets of lilting tuneful songs of love and beauty, there was no technique in language that Sankara did not take up; and whatever literary form he took up, he proved himself to be a master in it. From masculine prose to soft feminine songs, from marching militant verses to dancing songful words, be he in the halls of the Upanishad commentaries or in the temple of the Brahma-sutra expositions, in the amphitheatre of his Bhagavad-geeta discourses, or in the open flowery fields of his devotional songs, his was a pen that danced to the rhythm of his heart and to the swing of his thoughts.

But pen alone would not have won the war of culture for our country. He showed himself to be great organizer, a farsighted diplomat, a courageous hero and a tireless servant of the country. Selfless and unassuming, this mighty angel strode up and down the length and breadth of the country, serving his motherland and teaching his countrymen to live up to the dignity and glory of Bharat. Such a vast programme can neither be accomplished by an individual nor sustained without institutions of great discipline and perfect organisation. Establishing the mutts, opening temples, organizing halls of education, and even prescribing certain ecclesiastical codes, this mighty master left nothing undone in maintaining what he achieved.

Periods of revival, especially in art and culture, are generally preceded by a renewed enthusiasm in the ancient books and this is as it should be. With reference to the period in which it is happening, revivalism is a revolution, but at the same time, with reference TO the past, it is only an attempt to imbibe the best that was, in order to reinforce the present with it. The cultural atmosphere in our country at this moment is ripe for a revivalist movement and many brilliant signs of it are everywhere, evident to all those who have got eyes to see. Deep philosophical discussions are heard now and then today even in the most unexpected sitting rooms in the busy cities. All over the country, crowds of the faithful are increasingly attending the shrines. Discourses upon the scriptures are becoming increasingly popular, and in very many of them the discussions are often found to be serious and deep. In the context of this newfound enthusiasm in the country we should presume that we are already in an era of cultural revival.

Against such a background, the life and work of Adi Sankara are indeed an inspiration to this country to relive the glorious Hindu Culture. The Acharyas of old never found leisure in their lifetime to write their autobiography or celebrate their birthdays: self-effacement was the very spirit that governed their life and activities. Therefore, all that we know about our great rishis and mystic scholars are but traditions clothed in exaggeration, together describing an adorable creature fleeting across history, an ethereal light that flashes across in its own blinding glory.

There are a number of books dealing with the life and work of Adi Sankara in Sanskrit. Among them, Srimad Sankara Digvijayam of Sri Swami Vidyaranya, the incomparable pontiff of Sringeri in the 14th century, is the most popular and outstanding work. The deep knowledge and vast study of Sri Madhava, while he was the Prime Minister of the Vijayanagar Empire, matured themselves in Sri Swami Vidyaranya to yield to posterity this immortal masterpiece.

Today, there is throughout the country a great enthusiasm in Sankara; the signs of revival are everywhere around us. On Sri Sankara Jayanthi day, we find celebrations everywhere. Unfortunately, none of the thundering platforms successfully brings out the personality of this great master from Kalady. A lot is known of Adi Sankara, but very few know of ‘The Sankara’. The more we learn to adore him, not as a divine incarnation but as a sincere man inspired to serve the country and reconquer the nation from its slavery to alien ideologies, the more we shall successfully pay our tribute to our own culture.

*******